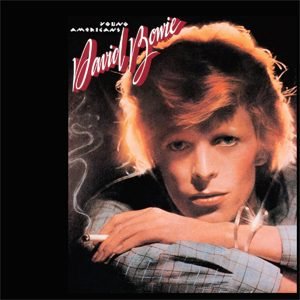

By the time Young Americans arrived in 1975, David Bowie had already cycled through multiple artistic personas—from the enigmatic folkie of Space Oddity to the glittering alien rock star of Ziggy Stardust and the decadent, dystopian cabaret of Diamond Dogs. Yet, with this album, Bowie executed one of his most radical transformations yet, shedding the theatricality of glam rock in favor of what he called “plastic soul.”

At its core, Young Americans was a bold foray into the world of American R&B, influenced by the likes of Philly soul and Motown. The album saw Bowie trading in his British art-rock roots for lush arrangements, swaggering horn sections, and gospel-infused backing vocals, courtesy of a young Luther Vandross. It was a sonic and stylistic pivot, one that placed him in conversation with Black American music traditions while also reflecting his own obsession with reinvention.

Bowie himself described the album as “the definitive split between Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke,” a bridge between the excess of glam and the cool detachment of his later Berlin Trilogy. In interviews, he spoke about being captivated by American culture, fascinated by the soul music he encountered while touring the U.S., and eager to push himself into unfamiliar musical territory. With Young Americans, Bowie wasn’t just experimenting—he was actively reshaping his own identity in real time.

Sonic Exploration

From the opening moments of Young Americans, it’s clear that David Bowie has traded the angular, dystopian rock of Diamond Dogs for something more expansive and groove-oriented. The album’s sonic palette is lush and sophisticated, drenched in the warmth of American soul and R&B, but still filtered through Bowie’s own restless artistic vision.

Production Quality

Produced by Tony Visconti, Young Americans boasts a sleek, polished sound that stands in stark contrast to the rawer textures of Bowie’s earlier work. The album was largely recorded at Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia, a hub for the city’s emerging “Philly soul” movement, which had been pioneered by producers like Gamble and Huff. This setting played a crucial role in shaping the album’s sonic identity—crisp drum beats, shimmering string sections, and a vibrant horn section give the record a refined yet energetic feel.

The production is neither lo-fi nor overly slick; instead, it strikes a balance that allows the organic energy of the performances to shine through. Unlike many soul records of the era, which leaned into smooth perfectionism, Young Americans maintains an edge—there’s a slight looseness to the rhythm section, an occasional rawness in Bowie’s vocals, a subtle sense that these songs are being performed in real time rather than meticulously sculpted in post-production. This approach lends the album an authenticity that prevents it from feeling like mere pastiche.

Musical Arrangements

One of the album’s standout features is its intricate and dynamic arrangements. Guitarist Carlos Alomar, who would go on to become a key Bowie collaborator, lays down tight, funky rhythms that drive much of the album’s groove. His playing, particularly on tracks like Fame and Fascination, is both infectious and restrained, leaving space for the rhythm section to breathe.

Meanwhile, the horn arrangements—delivered with punch and precision—bring a brassy, celebratory flair to tracks like Young Americans and Right. These flourishes, combined with the swelling string arrangements, elevate the music beyond simple rock or soul structures into something more cinematic.

Vocally, Bowie pushes himself into new territory. While his signature theatricality is still present, he adopts a more soulful delivery, frequently supported by an exceptional backing vocal ensemble, including a young Luther Vandross. This gospel-infused approach reaches its peak in Somebody Up There Likes Me, where Bowie’s call-and-response exchanges with the backing vocalists create a sense of spiritual urgency.

Genre Elements

While Young Americans is often categorized as a soul album, it never fully commits to traditional soul conventions. Instead, it exists in a hybrid space—Bowie’s version of R&B is infused with art-rock sensibilities, subtle avant-garde touches, and moments of glam rock residue.

The influence of Philly soul is most apparent in tracks like Win and Can You Hear Me, which feature smooth, melancholic melodies and luxurious arrangements. At the same time, funk makes its presence known—particularly in Fame, co-written with John Lennon and Carlos Alomar. The track’s sparse, syncopated rhythm and Bowie’s half-sung, half-spoken vocals foreshadow the darker, more experimental funk explorations he would pursue later in Station to Station.

Yet, for all its soul influences, Young Americans remains unmistakably a Bowie album. His lyrical themes—alienation, fleeting romance, political disillusionment—are far removed from the more direct storytelling of classic R&B. He’s not simply imitating a genre; he’s absorbing its textures and reconfiguring them into something uniquely his own.

Lyrical Analysis

While Young Americans may be Bowie’s most sonically direct album up to this point, its lyrics are anything but straightforward. Beneath the slick veneer of its “plastic soul” sound, the album wrestles with themes of identity, disillusionment, and the fading idealism of the 1970s. Bowie’s words dart between abstraction and sharp social critique, creating a lyrical landscape that feels both intimate and detached, personal yet universal.

Themes and Messages

At its heart, Young Americans is an album about America—both the romanticized vision of it and the reality that lurks beneath. The title track sets the tone, painting a restless portrait of youth caught between hope and cynicism. Bowie’s lyrics brim with fragmented imagery: a girl in crisis, a couple struggling to connect, references to Richard Nixon and McCarthyism. The song isn’t just about young love; it’s about the slow erosion of post-war optimism.

This tension between aspiration and disillusionment runs through the album. Win and Can You Hear Me explore themes of longing and emotional distance, delivered with a deceptive smoothness. Fascination and Somebody Up There Likes Me touch on the seductive power of fame and influence, with Bowie slipping into the role of an enigmatic observer.

Perhaps the most striking moment of cynicism comes with Fame, co-written with John Lennon. Here, Bowie strips away the album’s romanticism and delivers a scathing takedown of celebrity culture. The lyrics are sparse and biting:

“Fame, what you like is in the limo / Fame, what you get is no tomorrow.”

It’s a stark realization from an artist who had, by this point, experienced both the highs and lows of global stardom.

Lyrical Depth

Bowie rarely tells linear stories in Young Americans. Instead, he employs a cut-up, collage-like approach, blending evocative phrases and snapshots of life into something more impressionistic. The lyrics feel like overheard conversations, fleeting thoughts, or disjointed scenes from a film—reflecting the fast-moving, media-saturated world Bowie was absorbing.

Win and Somebody Up There Likes Me unfold like cryptic sermons, their meanings slipping just out of reach. Bowie uses repetition and ambiguity to enhance their hypnotic, almost trance-like quality. This approach makes the album’s lyrics feel more open-ended—inviting interpretation rather than spelling out a clear message.

Emotional Impact

One of Young Americans’s most fascinating contradictions is the way its lyrics oscillate between deep emotional intensity and a kind of cool detachment. At times, Bowie sounds desperate for connection—pleading for love in Can You Hear Me, whispering hypnotically in Win. Yet, elsewhere, he pulls away, observing life at a distance, almost as an outsider looking in.

This emotional push-and-pull adds to the album’s allure. It makes Young Americans feel both intimate and impersonal, as if Bowie is singing about universal experiences but never fully surrendering himself to them. His vocal delivery shifts accordingly—sometimes raw and pleading, other times aloof and ironic. The effect is a collection of songs that evoke longing, nostalgia, and unease in equal measure.

Cohesion and Flow

For an album built on reinvention, Young Americans maintains a surprisingly strong sense of cohesion. Though David Bowie shifts between moods and styles—from the sweeping grandeur of Philly soul to the stripped-down funk of Fame—there’s a unifying thread in both its sound and themes. The album flows like a restless, late-night odyssey through the American experience, mirroring Bowie’s own fascination with the country’s music, politics, and cultural contradictions.

Track Progression

The album’s sequencing plays a crucial role in how it unfolds emotionally. It opens with the title track, Young Americans, a sprawling, exuberant yet subtly cynical anthem that sets the stage for the album’s themes of longing, identity, and disillusionment. This is followed by Win, a downtempo, hypnotic number that shifts the energy inward, as if the initial rush of excitement has given way to self-reflection.

The transitions between songs are smooth, yet they carry an unpredictable edge—each track feels distinct but never out of place. Fascination injects funkier, danceable energy into the mix, keeping the momentum alive before Right pulls things back into a slow-burning groove. This back-and-forth between high-energy and introspective moments prevents the album from feeling monotonous.

As the album reaches its final stretch, Somebody Up There Likes Me swells with a near-messianic intensity, Bowie crooning over gospel-infused backing vocals and shimmering instrumentation. Then comes Across the Universe, the album’s most jarring shift. The John Lennon-penned Beatles cover, reinterpreted with an almost theatrical grandeur, disrupts the album’s original material and has long been debated by fans and critics as either a fascinating experiment or a misplaced detour.

But Bowie quickly regains focus with Can You Hear Me, a tender and soulful ballad that feels like a final moment of emotional vulnerability before the album closes with Fame. As the final track, Fame is a perfect send-off—cool, sharp-edged, and dripping with irony. It strips away the lushness that came before, leaving the listener with something raw, rhythmic, and biting.

Thematic Consistency

Despite its stylistic variety, Young Americans never feels disjointed. Its core themes—aspiration, uncertainty, desire, and identity—persist throughout, making the album feel like a single, immersive experience rather than a collection of disparate songs.

Bowie’s ability to weave together personal introspection and broader cultural commentary is what holds everything together. Whether he’s exploring relationships (Win, Can You Hear Me), societal disillusionment (Young Americans), or the emptiness of fame (Fame), there’s a sense that all these ideas are connected. It’s an album that examines America from different angles—sometimes in admiration, sometimes in critique, but always with a sense of curiosity and reinvention.

Even Across the Universe, for all its divisiveness, still fits within the album’s larger themes of searching for meaning in a world that feels chaotic and overwhelming. It may be the album’s least essential track, but thematically, it aligns with Bowie’s fascination with both transcendence and disillusionment.

Standout Tracks and Moments

Though Young Americans is a remarkably cohesive album, certain tracks stand out for their artistic ambition, emotional resonance, or sheer innovation. Bowie’s first deep dive into soul and funk wasn’t just an aesthetic experiment—it was a bold reinvention that produced some of his most intriguing and enduring work.

Young Americans

The title track is not only one of the album’s highlights but one of the most defining songs of Bowie’s career. Clocking in at over five minutes, Young Americans is a sweeping, cinematic piece that captures the tension between youthful idealism and harsh reality. With its infectious rhythm, blaring horns, and gospel-infused background vocals, the song is a dazzling display of Bowie’s newfound embrace of soul music.

Fame

If Young Americans is the album’s thematic centerpiece, Fame is its most radical musical statement. Co-written with John Lennon and guitarist Carlos Alomar, the track is a stark departure from the lush arrangements of the rest of the album, built around a minimalist, slinky funk riff that would influence generations of artists.

What makes Fame so compelling is its hypnotic groove, with Alomar’s guitar locking into a tight, cyclical rhythm that gives the track an almost mechanical feel. Bowie’s vocals shift between sneering falsetto and detached coolness, mirroring the song’s sardonic take on celebrity culture. Lennon’s presence—his distorted backing vocals and sardonic energy—adds an extra layer of irony, making Fame not just a funk classic but also one of Bowie’s sharpest critiques of the industry that made him a star.

Win

One of the album’s most underrated moments, Win is a mesmerizing slow-burn, showcasing Bowie’s ability to blend soul stylings with a haunting, almost dreamlike atmosphere. The track’s smooth, liquid guitar lines and lush orchestration give it a hypnotic quality, while Bowie’s vocal performance is deeply emotive, wavering between tenderness and quiet desperation.

Lyrically, Win is both seductive and ambiguous. The repeated refrain, “All you’ve got to do is win”, can be interpreted as a mantra of ambition or a cynical comment on survival in an unforgiving world. The song’s delicate interplay between optimism and melancholy makes it one of the album’s most emotionally affecting moments.

Somebody Up There Likes Me

This track is where Bowie fully embraces the grandeur of soul music, with sweeping instrumentation, commanding vocal delivery, and an almost sermon-like intensity. The song’s lyrics, with their vague references to power, control, and influence, add to its mystique—Bowie sounds both prophetic and elusive, delivering lines like “He’s everybody’s token, on everybody’s wall” with a mix of admiration and skepticism.

It’s also one of the album’s best examples of how Bowie utilized his backing vocalists—Luther Vandross and others provide a rich, gospel-inspired counterpoint to Bowie’s lead, creating a layered, almost spiritual listening experience.

Memorable Moments

The Breakdown in Young Americans – Midway through the title track, Bowie’s voice drops into a smoky, spoken-word passage: “Ain’t there one damn song that can make me… break down and cry?” It’s a raw, almost theatrical moment that punctures the song’s joyous energy, revealing an undercurrent of exhaustion and frustration beneath its danceable groove.

The Vocal Experimentation in Fame – Bowie’s voice shifts unpredictably, moving from clipped, robotic phrasing to stretched-out falsettos (“Faaame!”). The vocal manipulations, combined with Lennon’s eerie, echoed “Fame, fame, fame” in the background, create an unsettling yet addictive atmosphere.

The String Swells in Win – The moment when the strings rise in Win, just as Bowie croons “All you’ve got to do is win”, is one of the album’s most hypnotic passages. The arrangement, combined with the slow, deliberate pacing of the track, makes it feel almost cinematic.

Luther Vandross’s Influence on Fascination – A funk-driven track built around a riff that originated in Vandross’s earlier song Funky Music (Is a Part of Me), Fascination is one of the album’s most infectious grooves. The backing vocals, particularly Vandross’s contributions, give the song an undeniable energy.

Artistic Contribution and Innovation

When Young Americans was released in 1975, it marked not only a turning point in David Bowie’s career but also a unique moment in the evolution of rock and soul music. By stepping away from the glam rock that had defined his early ’70s output and immersing himself in the rich textures of American R&B, Bowie both embraced and subverted genre conventions. The album was neither a straightforward soul record nor a traditional rock album; instead, it existed in a hybrid space, fusing elements of both while remaining distinctly Bowie.

Place in Genre/Industry

At a time when rock was still dominated by blues-based hard rock and progressive excess, Young Americans stood out as a daring pivot. Few white rock artists had attempted to engage with soul and R&B in such an immersive way—while artists like The Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton had drawn from Black American music, their approach was more blues-centric, whereas Bowie dove headfirst into the contemporary sound of Philly soul.

This move was risky. Soul music had a deeply rooted cultural and historical significance, and Bowie, as a British rock star, risked coming across as opportunistic. However, his approach—working with Black musicians, recording in a legendary soul studio (Sigma Sound in Philadelphia), and treating the genre with genuine respect and curiosity—helped Young Americans avoid feeling like mere appropriation. Instead, it was a bold artistic experiment that bridged cultural and musical gaps, introducing elements of soul and funk to a rock audience that may not have otherwise engaged with them.

The album’s impact extended beyond Bowie’s own career. It foreshadowed the growing influence of funk and R&B on rock music, a trend that would become even more pronounced by the late ’70s and early ’80s. Artists like Prince, Talking Heads, and even The Clash would later incorporate funk elements into their sound, but Bowie was among the first mainstream rock artists to fully commit to the fusion.

Innovation

The Fusion of Rock and Soul

While crossover efforts between rock and R&B had existed before (The Beatles’ Rubber Soul, The Stones’ Some Girls), Young Americans was one of the first albums where a rock artist fully immersed themselves in the contemporary soul sound of the time. The influence of Philly soul—lush orchestrations, tight grooves, gospel-inspired backing vocals—wasn’t just a surface-level aesthetic choice; it was deeply integrated into the songwriting and production.

Minimalist Funk in Fame

Perhaps the album’s most forward-thinking moment is Fame, co-written with John Lennon and Carlos Alomar. Built around a stripped-down, syncopated guitar riff, the song deconstructs the lush sound of the rest of the album, replacing it with something raw, almost skeletal. This approach was groundbreaking—years before the minimalist funk of Prince or the Talking Heads, Bowie was already playing with space, groove, and rhythmic tension in a way that was ahead of its time.

The Use of Avant-Garde Lyricism in a Soul Context

Bowie’s lyrics had always been surreal and fragmented, borrowing from the cut-up techniques of William S. Burroughs. What made Young Americans unique was how he applied this approach to a genre known for direct storytelling. Instead of clear narratives about love and heartache, Bowie delivered abstract, collage-like impressions—references to Nixon, Brando, and political paranoia slipped between phrases about young love and disillusionment. This fusion of poetic ambiguity with soul’s emotional directness created something entirely new.

Luther Vandross’s Early Influence

The presence of a young Luther Vandross on backing vocals (and as a co-writer of Fascination) was another key innovation. Vandross, who would later become an R&B icon, brought a level of vocal sophistication that elevated the album’s authenticity. His involvement wasn’t just a footnote—it was a glimpse into the future of R&B, as Vandross would go on to define the genre’s smooth, sophisticated sound in the 1980s.

Blurring the Line Between Authenticity and Performance

One of the most intriguing aspects of Young Americans is how Bowie approached soul music not as an artist simply paying homage, but as a performer slipping into yet another character. He coined the term “plastic soul” to describe his take on the genre—a phrase that acknowledged both the sincerity and the artificiality of his transformation. This self-awareness was part of what made Young Americans so unique: it was both a genuine engagement with a new sound and a reflection on the very act of musical reinvention.

Closing Thoughts

Young Americans stands as one of David Bowie’s most fascinating reinventions—an audacious leap into the world of soul and R&B that not only expanded his artistic range but also challenged the boundaries of genre itself. With its lush production, intricate arrangements, and thought-provoking lyrics, the album showcases Bowie’s ability to absorb musical influences and reshape them into something uniquely his own.

Strengths

Genre Experimentation: Bowie’s immersion in Philly soul and funk was ambitious, and he pulled it off with style. The album’s blend of sophisticated grooves and avant-garde lyricism remains one of its strongest attributes.

Standout Tracks: Songs like Young Americans, Fame, and Win are masterclasses in mood, melody, and reinvention, proving Bowie’s adaptability as a vocalist and songwriter.

Strong Collaborations: The presence of musicians like Carlos Alomar and Luther Vandross adds authenticity and depth to the album’s sound.

Emotional and Thematic Depth: Beneath the infectious grooves, the album wrestles with themes of identity, aspiration, and disillusionment, making it more than just a stylistic exercise.

Weaknesses

Pacing Issues: The album’s flow, while generally strong, has a few moments where the energy dips—particularly with Across the Universe, which, though interesting, feels somewhat out of place compared to the rest of the album.

Not as Sonically Revolutionary as Later Albums: While Young Americans is a bold stylistic shift, it doesn’t quite achieve the level of groundbreaking innovation that Bowie would explore in Station to Station and beyond.

Official Rating: 8/10

While Young Americans isn’t Bowie’s most revolutionary work, it’s an essential piece of his artistic evolution. It captures him in transition—boldly shedding one skin while preparing to don another. The album’s biggest achievement lies in how successfully it integrates soul music into Bowie’s own artistic lexicon, proving that reinvention isn’t just about aesthetic shifts, but about deeply engaging with new musical landscapes.