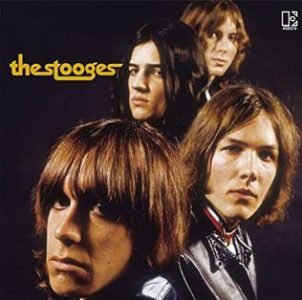

When The Stooges released their self-titled debut in August 1969, it did not arrive with the polish or pretense that marked many of its contemporaries. Instead, it came raw and loud, dragging a primal energy into a rock landscape that was increasingly drawn to complexity and idealism. At the time, bands like The Beatles were winding down their psychedelic experiments, and Led Zeppelin had just begun shaping the future of hard rock. In contrast, The Stooges looked backward and inward, tapping into something more primal and immediate.

This was the first album from a group that would later become known as one of the cornerstones of punk rock. Yet in 1969, The Stooges were more of a wild card than a movement. There was no template for what they were doing. Iggy Pop, Ron Asheton, Scott Asheton, and Dave Alexander brought a sound that was abrasive and unrefined, but deeply intentional. With John Cale of the Velvet Underground producing, the band set out to capture the essence of chaos and teenage boredom, not through poetry or narrative, but through mood and repetition.

Sonic Exploration

The production on The Stooges walks a tightrope between the deliberate and the chaotic. Handled by John Cale, who had recently left the Velvet Underground, the album’s sound is gritty and immediate. It never tries to clean up the band’s rough edges. Instead, it leans into them. The recording feels almost live, as if the band is playing in a half-empty room with the amps turned up too loud. This lo-fi approach suits the mood perfectly. It complements the band’s raw, aggressive attitude and reinforces the sense that what you’re hearing is something unfiltered.

Musical Arrangements

The arrangements on the album are intentionally minimal. Ron Asheton’s guitar work is simple but powerful, relying on repetition to build tension. Tracks like “1969” and “I Wanna Be Your Dog” showcase riffs that loop with hypnotic persistence. Rather than shifting through elaborate chord progressions, Asheton rides a few notes into the ground, creating a trance-like effect. His playing is thick and distorted, serving more as a blunt instrument than a melodic guide. Meanwhile, Dave Alexander’s bass lines keep everything anchored, often mirroring the guitar to build a wall of sound rather than a melodic counterpoint.

Iggy Pop’s vocals are central to the record’s identity. He doesn’t sing in the traditional sense. Instead, he snarls, sneers, and mutters his way through the lyrics, sounding more like a character in a punk play than a frontman of a rock band. His voice cuts through the mix, not with clarity but with presence. There’s a physicality to his delivery that matches the band’s muscular sound.

As for genre, The Stooges straddles the line between garage rock and proto-punk. There are traces of blues and hard rock, but everything is stripped of excess. It’s punk before punk had a name. The album doesn’t try to blend genres in a showy way. It sticks to its lane and pushes it to the limit. What makes it feel fresh is the sheer audacity of its approach. In an era when rock was often about virtuosity, The Stooges chose attitude over complexity. And in doing so, they laid the groundwork for a movement that wouldn’t fully bloom until years later.

Lyrical Analysis

The lyrics on The Stooges are as raw and stripped-down as the music. They reflect a world of adolescent frustration, longing, and restless energy. Rather than building complex narratives or poetic metaphors, the band opts for directness. The themes are clear: boredom, desire, rebellion, and a craving for something—anything—that feels real. This bluntness is not a flaw; it’s part of the album’s core identity. It’s the language of someone who doesn’t want to think too hard, who just wants to feel something in a world that feels numb.

“1969” opens the album with a simple but pointed declaration: “Well it’s 1969, okay / All across the USA.” The repetition of the year sets the tone, not as a celebration, but as a statement of malaise. The song isn’t about cultural milestones or peace and love. It’s about feeling stuck in a time that promises more than it delivers. The message is less about specific politics and more about a general discontent that runs just under the surface.

“I Wanna Be Your Dog” is arguably the album’s most iconic track, and its lyrics are as provocative as its title suggests. The song flips the idea of romantic or sexual longing into something darker and more submissive. The refrain is repeated with relentless force, turning desire into obsession. There’s little subtlety here, but that’s what gives it power. The simplicity becomes a chant, a kind of emotional surrender that’s both unsettling and strangely honest.

Recurring motifs across the album include isolation, repetition, and physicality. In “No Fun,” Iggy voices the kind of nihilism that would later become a punk staple: “No fun my babe, no fun / No fun to hang around / Feelin’ that same old way.” It’s a complaint, a cry, and a challenge, all rolled into one. There’s no resolution offered—just the statement of a feeling that refuses to change.

Lyrical Depth

In terms of lyrical depth, the album doesn’t aim for complexity in a traditional sense. There are no layered meanings or hidden metaphors waiting to be unpacked. Instead, the emotional impact comes from the raw honesty. The lyrics evoke restlessness and desperation, not through storytelling, but through rhythm and tone. They aren’t meant to be dissected in a classroom—they’re meant to be felt, shouted, and maybe even spit into the void.

Cohesion and Flow

The Stooges doesn’t follow a traditional arc or narrative, but there’s a strange unity in its chaos. The album’s progression isn’t built on a story unfolding across tracks. Instead, it relies on mood and repetition to create a kind of hypnotic consistency. Each song seems to emerge from the same dark, sticky basement of emotion—boredom, lust, frustration—without trying to resolve or escape it. That choice, whether intentional or instinctive, gives the record a rough but steady flow.

The tracklist opens with “1969,” setting the tone with its sense of disillusionment, and closes with “Little Doll,” which doesn’t so much offer closure as it does one final burst of restless energy. In between, the record doesn’t shift gears dramatically. There are no ballads, no interludes, no grand experiments. Songs like “No Fun,” “Real Cool Time,” and “Ann” stick to their core ideas and don’t wander far. This creates a kind of emotional loop—the same feelings are expressed over and over, but each time with a slightly different edge.

That repetition may test the patience of some listeners. There are points where the album threatens to blur into itself. “We Will Fall,” the one significant departure in tone and length, offers a spacey, droning atmosphere that feels at odds with the rest of the album. Its meditative chant and eerie violin lines stretch on for over ten minutes, which some might see as a welcome change, while others might find it stalls the album’s otherwise tight pacing. It’s the one moment that feels like it belongs to another band—or at least another idea.

Thematic Consistency

Despite that, the album’s themes and sonic palette stay largely consistent. The raw production, primal riffs, and snarling vocals hold the tracks together. Even when individual songs don’t stand out melodically, they contribute to the record’s overall feel. There’s a kind of stubborn cohesion here. The Stooges weren’t interested in variety for its own sake. They found a sound and stuck with it, hammering the same emotional note until it broke.

Standout Tracks and Moments

Among the eight tracks on The Stooges, a few rise above the rest—not because they abandon the band’s raw formula, but because they refine it just enough to leave a lasting mark.

I Wanna Be Your Dog

“I Wanna Be Your Dog” is the album’s centerpiece and its most iconic moment. From the first clang of the distorted piano chord, it announces itself with menace. Ron Asheton’s riff is one of rock’s great minimal statements—simple, brutal, and hypnotic. The way the guitar locks in with Dave Alexander’s bass and Scott Asheton’s relentless drumming creates a pulse that feels less like a groove and more like a threat. It’s not just the music that makes it stand out; it’s the way Iggy Pop leans into the desperation of the lyrics. He doesn’t sing so much as crawl through the song. That tension between submission and violence captures the album’s core.

No Fun

“No Fun” is another highlight, showcasing the band’s ability to turn repetition into something cathartic. The song loops a basic chord structure and lyrical refrain, but with every cycle it grows heavier, as if the weight of boredom is becoming too much to bear. Iggy’s delivery moves from taunting to exhausted, making the listener feel the song’s emotional drag. It’s a prime example of how the band used simplicity to their advantage.

1969

Then there’s “1969,” the opening track, which sets the tone perfectly. Its stuttering riff and sharp, unadorned lyrics capture a sense of disillusionment that was, and still is, easy to relate to. The moment where Iggy spits out “Another year with nothing to do” feels like a punchline with no joke—just a raw expression of aimlessness.

We Will Fall

Even “We Will Fall,” though divisive, holds a unique place. Its drawn-out, droning chant and haunting violin part create a trance-like atmosphere unlike anything else on the record. Whether it’s seen as a brave experiment or an indulgent detour, it’s hard to deny that it adds texture to the album’s otherwise tight focus.

Artistic Contribution and Innovation

When The Stooges dropped in 1969, it didn’t fit neatly into the landscape of the time. Psychedelic rock was still echoing through mainstream consciousness, and progressive rock was beginning to stretch the limits of composition and technical skill. In that context, The Stooges felt like a rejection of rock’s growing sophistication. They weren’t interested in virtuosity or studio trickery. Instead, they stripped everything down to its most essential parts—noise, rhythm, attitude—and in doing so, helped carve out a new path for rock music.

Though the term “punk” wouldn’t become part of the music lexicon for several more years, this debut laid down many of the genre’s blueprints. The album’s blunt instrumentation, sneering vocals, and minimalist structure pushed back against the excesses of the late ‘60s. It didn’t try to impress; it tried to provoke. That, in itself, was radical. Few albums at the time were so brazen in their disregard for polish or complexity.

Innovation

The innovation here lies in the band’s commitment to a sound that felt more like a mood than a musical style. John Cale’s raw production gave the songs an unvarnished, almost confrontational presence. The guitars weren’t layered or sculpted; they were jagged and loud. The lyrics weren’t poetic; they were visceral. This directness felt new, not because no one had ever been loud or brash before, but because The Stooges made those qualities the entire point.

They also challenged the idea of what a rock frontman could be. Iggy Pop’s unhinged delivery and confrontational stage presence would go on to influence generations of performers, from Johnny Rotten to Kurt Cobain. His performance on this album—equal parts bark, sneer, and croon—wasn’t technically impressive, but it was undeniably magnetic.

What’s remarkable in hindsight is how many future sounds were hinted at here. Elements of noise rock, post-punk, and industrial music can all trace part of their DNA back to The Stooges. At the time of its release, the album was dismissed by many critics and overlooked by radio. But history has vindicated it. While it didn’t chart high or spark a movement overnight, it eventually became a cornerstone for what rock could be when stripped of its ego.

Closing Thoughts

The Stooges is an album that thrives on instinct. It doesn’t aim for perfection, and it rarely concerns itself with precision. Instead, it captures something far more elusive: raw, unfiltered energy. The strengths of the record lie in its uncompromising attitude, its stripped-down sound, and its ability to communicate boredom, lust, and frustration without artifice. Iggy Pop and his bandmates weren’t trying to be clever—they were trying to be real, and in doing so, they ended up sounding like the future.

That said, the album isn’t without its weaknesses. The repetitive structures and limited melodic variation may not appeal to every listener, especially those who prefer a more dynamic or polished sound. “We Will Fall,” while interesting in concept, can feel like a pacing misstep in an otherwise tight collection. These are not dealbreakers, but they do reveal the growing pains of a band still finding its footing.

Still, the impact of The Stooges can’t be overstated. It didn’t explode on release, but over time it became a foundational text for punk, garage, and alternative rock. For listeners willing to meet it on its own terms, the album offers something honest, jarring, and strangely timeless. It’s a record that doesn’t try to explain itself—it just exists, loud and unapologetic.

Official Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the album’s enduring influence, its artistic boldness, and its sheer force of personality. It’s not flawless, but its flaws are part of its charm. The Stooges may not have been fully understood in its time, but it helped shape the sound and spirit of rock for decades to come.