David Bowie stands as one of the most transformative figures in modern music, fashion, and pop culture. From the moment he arrived on the scene in the late 1960s, Bowie refused to conform to any single artistic mold. His music challenged genre boundaries, blending rock, folk, electronic, and avant-garde influences, while his visual presentation often felt ahead of its time—infusing high fashion with elements of theater, futurism, and surrealism. Bowie’s impact is undeniable: he revolutionized how an artist could not only perform but also reshape identity, using his own image as a canvas for experimentation and self-expression.

Central to Bowie’s legacy is his near-constant reinvention, best embodied by the string of personas he crafted throughout his career. These personas were not merely theatrical costumes or marketing tools; they were integral to his artistic identity, representing different aspects of his creative psyche and allowing him to explore new sonic landscapes without being tethered to one version of himself. Whether it was the glam-rock alien Ziggy Stardust, the icy and detached Thin White Duke, or the apocalyptic Halloween Jack, each persona reflected not only the evolution of Bowie as an artist but also broader cultural shifts in music, fashion, and social attitudes.

The Origins of Reinvention: Early Bowie (1960s)

The Mod and Folk Singer

Before David Bowie became the genre-defying icon known for his flamboyant personas, he emerged in the 1960s as a young musician deeply rooted in British pop culture’s evolving landscape. This period was defined by Bowie’s exploration of various musical and visual identities, though it lacked the high-concept, theatrical elements he would later become famous for. Influenced by the burgeoning British Invasion, mod culture, and folk music, Bowie was still searching for his voice—both literally and figuratively.

In his early years, Bowie gravitated toward the mod scene, which had taken London by storm. Mod culture emphasized sharp fashion, modernist aesthetics, and a love for American rhythm and blues, elements that shaped Bowie’s early style. Musically, his debut album, David Bowie (1967), showcased an artist with an eclectic palette but little sense of direction. The record was a strange mix of music hall, cabaret, and quirky pop—far removed from the rock anthems or experimental sounds he would later pioneer. At this point, Bowie’s persona was that of a dapper young mod, borrowing from the likes of The Kinks and The Who, while his music leaned heavily on whimsical, almost theatrical storytelling.

Folk Music

As the 1960s progressed, Bowie’s ambitions grew. While he initially flirted with the mod movement, he soon became intrigued by the introspective depth of folk music, taking cues from artists like Bob Dylan and Donovan. This influence is particularly evident in Space Oddity (1969), the breakthrough single that would catapult Bowie into the mainstream. With its haunting tale of the astronaut Major Tom, “Space Oddity” married folk sensibilities with a growing fascination for space exploration and the future. It reflected the era’s optimism for technological advancement, as well as a deep sense of isolation—a theme that would recur in Bowie’s later work.

“Space Oddity” also marked a critical turning point in Bowie’s career. It signaled the beginning of his transition toward more experimental sounds and visuals. Around this time, his fascination with avant-garde theater, mime, and visual art began to surface, setting the stage for the dramatic persona shifts that would define the next decade of his career. The 1960s Bowie—mod and folk singer—was an artist searching for a distinctive voice in a crowded musical landscape, but this era laid the groundwork for the radical transformations that would follow.

In the span of a few years, Bowie had dabbled in pop, mod, and folk, establishing himself as a restless creative force. While still far from the seismic reinventions of Ziggy Stardust or the Thin White Duke, this early period was crucial in shaping Bowie’s approach to constant reinvention. It was here that the seeds of his chameleon-like artistry were first planted, hinting at the shape-shifting genius that was just around the corner.

Ziggy Stardust: The Alien Messiah (1972-1973)

Birth of Glam Rock

In 1972, David Bowie introduced the world to Ziggy Stardust, a glittering, androgynous alien rock star who would forever alter the course of music and pop culture. Ziggy was more than just a persona—he was a vehicle through which Bowie transformed rock music into a theatrical spectacle, ushering in the era of glam rock. With Ziggy’s arrival, Bowie gave permission to a generation of artists and fans to embrace their individuality, pushing the boundaries of identity, gender, and artistry.

Ziggy Stardust was born from a fusion of Bowie’s influences: the wildness of early rock ‘n’ roll, the outrageous fashion of the avant-garde, and the science fiction fantasies of the late 1960s and early ‘70s. This persona, first immortalized on the seminal album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972), told the story of a bisexual, extraterrestrial rock star who comes to Earth to deliver a message of salvation but ultimately falls victim to his own fame. The album mixed elements of rock, glam, and proto-punk, with anthemic tracks like “Starman” and “Suffragette City” capturing Ziggy’s explosive charisma.

The Concept

At its core, Ziggy Stardust represented alienation, androgyny, and rebellion. Bowie’s creation tapped into the disillusionment of the early 1970s, a time when the utopian dreams of the 1960s had crumbled, leaving a generation searching for new idols and identities. Ziggy was the ultimate outsider—an alien who didn’t fit in but embraced his difference with unapologetic confidence. His otherworldly appearance, complete with vivid makeup, wild orange hair, and skin-tight, glittering costumes, broke down traditional gender norms, blending masculine and feminine aesthetics in a way that was both shocking and alluring.

The album itself was groundbreaking, but Ziggy truly came to life on stage. Bowie’s live performances as Ziggy Stardust were electrifying and theatrical, turning concerts into spectacles of light, sound, and self-expression. The Spiders from Mars, Bowie’s backing band, brought a hard-hitting rock edge to the music, but it was Bowie’s embodiment of Ziggy that left audiences spellbound. Songs like “Moonage Daydream” and “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide” weren’t just performed—they were lived out, as Bowie blurred the line between artist and persona, becoming Ziggy both on and off the stage.

Influence on Popular Culture

Ziggy’s influence on glam rock and popular culture was immediate and profound. The persona’s flamboyant style and unapologetic theatricality inspired a generation of artists to embrace showmanship and spectacle in their music. Musicians like Marc Bolan, Lou Reed, and Iggy Pop—already key figures in the burgeoning glam scene—found new inspiration in Bowie’s fearless transformation, while future stars like Madonna, Prince, and Lady Gaga would later cite Ziggy as a key influence on their approach to performance and identity. Bowie’s androgyny and fluid sexuality challenged rigid gender norms, making Ziggy Stardust a cultural lightning rod for conversations about sexual freedom and personal expression.

But by 1973, at the peak of Ziggy’s success, Bowie made the shocking decision to “kill” his creation. During a sold-out performance at London’s Hammersmith Odeon, Bowie famously announced, “This is the last show that we’ll ever do,” signaling the end of Ziggy Stardust. While fans were devastated, Bowie understood that Ziggy, who was created to burn bright and fast, had served his purpose. Bowie’s own sense of self was becoming consumed by the character he had created. By “killing” Ziggy, Bowie freed himself to evolve artistically, avoiding the trap of being defined by one persona.

Aladdin Sane: Glam with a Darker Edge (1973)

America and the Apocalypse

Following the success of Ziggy Stardust, David Bowie’s next persona, Aladdin Sane, emerged as a darker, more fractured figure—a reflection of Bowie’s experiences during his first major tour of the United States. If Ziggy Stardust had been an otherworldly rock star with a message of cosmic salvation, Aladdin Sane was his disillusioned, earthbound counterpart, grappling with the chaos, violence, and cultural fragmentation Bowie witnessed in 1970s America. Bowie described this character as “Ziggy goes to America,” and the resulting persona was a manifestation of both glam’s theatricality and the darker undercurrents of madness and apocalypse.

Aladdin Sane was Bowie’s response to the dissonance between the glitzy rock stardom he was achieving and the harsh realities of the world around him. The title of his 1973 album Aladdin Sane was a play on words, with “A Lad Insane” hinting at themes of mental instability and inner turmoil. The album’s lyrics reflect Bowie’s impressions of a rapidly changing, often violent America—an experience that left him feeling increasingly alienated. Tracks like “Panic in Detroit” and “Cracked Actor” explore urban unrest, hedonism, and existential dread, showcasing a world where fame, like everything else, comes with a cost.

While Ziggy Stardust had a cohesive narrative, Aladdin Sane was more fragmented and schizophrenic, echoing the instability Bowie felt during his frenetic tour schedule. Aladdin Sane’s persona embodied this disarray. The character’s sense of madness is woven into the album’s sonic structure, with its mix of glam rock riffs, avant-garde jazz flourishes, and jarring piano arrangements, most notably from avant-garde pianist Mike Garson on tracks like “Aladdin Sane (1913–1938–197?)” and “Lady Grinning Soul.” The music oscillates between the decadence of glam and an unnerving dissonance, reflecting the chaotic world Aladdin Sane inhabits.

The Concept

Thematically, Aladdin Sane explored the darker sides of fame and excess, contrasting Ziggy’s alien messiah persona with a rock star on the verge of losing his mind. Madness, violence, and disillusionment permeate the album. Songs like “Drive-In Saturday” depict a future society struggling to remember love and intimacy, while “Time” personifies the creeping menace of mortality, sung with an air of theatrical doom. Bowie painted a picture of a fractured world—one obsessed with fame but plagued by violence and decay. The album is steeped in a sense of impending apocalypse, with Bowie reflecting the increasing instability of the world around him.

Visually, Aladdin Sane is best remembered for the lightning bolt makeup that has since become one of Bowie’s most iconic images. The bolt, slashing across his face in vivid red and blue, symbolized the duality and split nature of the character—part glam superstar, part introspective artist unraveling under the pressures of fame and self-doubt. This image graced the album’s cover and became a lasting emblem of Bowie’s ability to blend music, fashion, and visual art into a cohesive artistic statement.

While Ziggy Stardust had embodied a more hopeful rebellion, Aladdin Sane took glam rock’s exuberance and infused it with darker, more disquieting themes. Bowie’s experiences in America during this period had exposed him to the country’s extremes—the glamorous highs of celebrity culture and the gritty lows of urban unrest and social fragmentation. These experiences were reflected in Aladdin Sane’s aesthetic: still glamorous, but with a haunting edge of madness and destruction.

Halloween Jack: The Rebel Outsider (1974)

The Dystopian Rock Star

In 1974, David Bowie introduced Halloween Jack, a rebellious, street-smart persona who was the central figure in his dystopian concept album Diamond Dogs. Moving away from the extraterrestrial glam of Ziggy Stardust and the fractured psyche of Aladdin Sane, Halloween Jack was a scrappier and more grounded character, living in a world that was distinctly darker and more chaotic. This persona was Bowie’s interpretation of a post-apocalyptic rock star, born out of his fascination with George Orwell’s 1984 and the dystopian worlds of both literature and reality.

Diamond Dogs was heavily influenced by Orwell’s bleak vision of the future in 1984, which Bowie had originally planned to adapt into a stage musical. When he couldn’t secure the rights, he reimagined the story through the lens of his own post-apocalyptic urban landscape. The album is set in the decaying city of Hunger City, a lawless, desolate place ruled by gangs and filled with depravity, corruption, and a sense of impending collapse. Halloween Jack is one of its residents—a charismatic outlaw and self-described “real cool cat” who leads a band of rebels against a totalitarian regime. Jack’s character embodied the dystopian survivalism of the album, representing a raw, rebellious energy in the face of societal decay.

The Concept

Visually, Halloween Jack was a departure from the ethereal androgyny of Ziggy Stardust. He was a more scrappy, street-smart figure with a punk edge, dressed in ragged clothes and sporting an eye-patch, his hair dyed bright red in a mullet-like style. Jack’s aesthetic was more grounded in urban grit, reflecting a rougher, more anarchic attitude. This persona carried an almost proto-punk vibe, foreshadowing the rebellious attitudes of the punk movement that was just beginning to take shape in the mid-1970s. While his previous personas had leaned into glam’s flamboyance and fantasy, Halloween Jack was Bowie’s way of embracing a harsher reality—a dystopian figure born out of societal collapse.

Diamond Dogs was filled with apocalyptic imagery and thematic explorations of control, chaos, and revolution. Songs like “Rebel Rebel” and “Diamond Dogs” captured the raw energy of this new persona, with a rock ‘n’ roll attitude that felt more defiant and dangerous than the slicker glam of his previous albums. “Rebel Rebel” in particular, with its iconic guitar riff and lyrics celebrating youthful rebellion and sexual freedom, became an anthem for outsiders everywhere, channeling the spirit of Halloween Jack’s refusal to conform.

A Shift in Style

This era also marked a significant shift towards a post-apocalyptic visual style in Bowie’s work, reflecting the increasing influence of dystopian fiction and proto-punk aesthetics. On stage and in promotional material, Halloween Jack roamed a crumbling urban jungle, surrounded by the debris of a fallen world. The Diamond Dogs tour, with its elaborate set pieces of dystopian skyscrapers and ruined cityscapes, further emphasized this move toward a darker, more decayed aesthetic. Jack’s ragged appearance and defiant attitude embodied a world where order had collapsed, and survival was for the scrappy, the clever, and the bold.

Musically, Diamond Dogs also pushed boundaries. The album was a transition point between the glam rock that had made Bowie a star and the funk and soul influences that would define his next major persona in the Young Americans era. The rough edges of proto-punk, the looming specter of fascism, and the concept of urban decay all fused together in Halloween Jack’s persona, making him a rebel outsider in every sense—fighting against authority, conformity, and even the glittery remnants of the glam scene Bowie had pioneered.

The Thin White Duke: The Cold Aristocrat (1976)

A Dark, Fragmented Soul

In 1976, David Bowie unveiled one of his most unsettling and controversial personas, The Thin White Duke. A stark departure from the glittering theatrics of Ziggy Stardust and the dystopian rebellion of Halloween Jack, the Duke was cold, emotionless, and aristocratic—an embodiment of alienation, decadence, and inner turmoil. The Thin White Duke reflected a darker, more fragmented side of Bowie’s psyche, one that mirrored his struggles with addiction, disillusionment, and existential despair. Through this persona, Bowie explored themes of fascism, emotional detachment, and the hollowness of fame, creating a character that felt disturbingly real and dangerously close to his own unraveling.

The Duke first emerged in Bowie’s 1976 album Station to Station, which was not only a sonic shift but also a psychological one. Musically, the album marked a transition from the funk and soul influences of Young Americans to a more European, art-rock sound, blending elements of krautrock, electronic music, and avant-garde experimentation.

However, it was the persona of the Thin White Duke that dominated the narrative. Dressed in a crisp white shirt, black waistcoat, and slicked-back hair, the Duke exuded a cold, aristocratic elegance. He was a figure devoid of warmth or empathy, singing about love as if it were nothing more than a clinical transaction, famously describing it as “a leper messiah” in the title track “Station to Station.”

The Concept

The Duke’s emotional detachment extended to his worldview. Throughout Station to Station and in interviews at the time, Bowie’s character flirted with themes of fascism and authoritarianism, making the persona even more controversial. The Duke embodied a darkly romanticized vision of power and control, a reflection of Bowie’s own flirtation with dangerous political ideas during a period of intense drug addiction and personal turmoil.

In both his music and public appearances, Bowie, as the Duke, seemed obsessed with fascist imagery, speaking in cryptic, detached tones about the allure of totalitarianism. This fascination, coupled with his increasingly erratic behavior due to cocaine addiction, blurred the lines between persona and person, leaving many to wonder if Bowie was becoming the very character he portrayed.

The Thin White Duke was not just a product of Bowie’s own personal demons but also a reflection of the cultural anxieties of the mid-1970s. In Europe, especially in West Berlin (where Bowie would soon relocate), there was a growing sense of dread, marked by political extremism, terrorism, and Cold War tensions. Bowie’s music during this period echoed the disillusionment and existential angst of a world grappling with the ghosts of the past and an uncertain future.

The Duke’s icy demeanor and references to fascism mirrored the specter of 20th-century totalitarianism, suggesting that beneath the surface of European sophistication lay a dangerous potential for chaos and destruction. This thematic depth resonated with the European art-house cinema and intellectual movements of the time, which were similarly preoccupied with alienation and the dark side of modernity.

Inner Turmoil

Though the Thin White Duke is often cited as one of Bowie’s most captivating personas, it also represents the darkest chapter of his life. Bowie was spiraling into cocaine addiction, living in a paranoid, fractured mental state, often isolated and barely sleeping. He later admitted to remembering very little from this period, especially the recording of Station to Station. The Duke, with his cold, fragmented soul, was a reflection of Bowie’s own emotional and psychological state—detached, disillusioned, and teetering on the edge of self-destruction. In many ways, Bowie was using the Duke to explore the darkest parts of himself, both artistically and personally.

Yet the persona was also highly controversial. Bowie’s flirtation with fascist imagery, including his infamous comment about Hitler being one of the first rock stars and the Nazi-like salute he allegedly gave at a London train station, stirred outrage and confusion. Many fans and critics were alarmed, questioning whether Bowie had gone too far in blending performance with reality. In hindsight, Bowie would later distance himself from these comments, attributing them to the toxic influence of drugs and a personal identity crisis. The Duke, it seemed, had pushed Bowie to a breaking point, both in terms of his public image and his personal health.

The Berlin Era and Beyond: The Everyman and Experimenter (1977-1979)

Low-Profile Bowie

After the turbulent years of The Thin White Duke, David Bowie made a dramatic shift in both his personal life and artistic approach, embracing a more introspective, low-profile persona during what would come to be known as his Berlin Era. This period, spanning from 1977 to 1979, saw Bowie leave behind the grandiose characters that had defined much of his early career, in favor of a minimalist, experimental approach to music and identity. Rather than embodying larger-than-life personas, Bowie adopted a stripped-down, almost anonymous presence—one that reflected his desire for reinvention and personal recovery.

The move to West Berlin in 1976 was a pivotal moment for Bowie. Seeking refuge from the chaos of Los Angeles and the destructive patterns of his fame, he relocated to the divided German city, which at the time was a cultural hub for avant-garde art and music. West Berlin, with its gritty, fractured atmosphere and burgeoning experimental scene, provided the perfect backdrop for Bowie’s creative rebirth.

Immersing himself in the city’s underground culture, Bowie collaborated with Brian Eno and producer Tony Visconti, drawing heavily from krautrock, electronic music, and the post-punk aesthetics of the time. The result was the Berlin Trilogy—three albums that marked a radical departure from his previous work, focusing on instrumental experimentation, electronic textures, and an introspective, fragmented narrative.

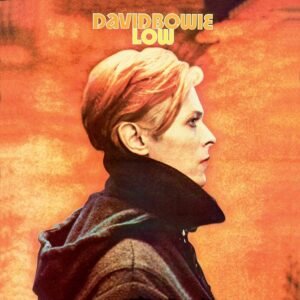

The Berlin Trilogy

The first album in the trilogy, Low (1977), set the tone for this new era. Sonically, it was a stark contrast to anything Bowie had done before, embracing minimalist structures and ambient soundscapes. The album’s first half featured short, fragmented songs with sparse lyrics, while the second half delved into moody, instrumental compositions influenced by the electronic innovations of German bands like Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream. Low was deeply personal, reflecting Bowie’s own struggles with addiction, alienation, and his need to rebuild. While the album may not have had a defined character like Ziggy Stardust or the Thin White Duke, it revealed Bowie’s internal landscape—fragmented yet searching for clarity.

Heroes

“Heroes“ (1977), the second album in the trilogy, was more outwardly optimistic but still maintained a sense of emotional distance and experimentalism. The title track, inspired by the sight of lovers kissing by the Berlin Wall, became an anthem of resilience and hope in a divided world. Yet, even in its anthemic glory, “Heroes” was a far cry from the bombast of Bowie’s previous personas—it was more grounded, a reflection of human perseverance rather than cosmic fantasy.

The album combined Berlin’s industrial, post-punk energy with Bowie’s electronic experimentation, further solidifying his artistic shift toward a more low-profile, everyman persona. This was Bowie not as an alien or dystopian rock star, but as a reflective artist—a man trying to make sense of the fractured world around him.

Lodger

The final album in the trilogy, Lodger (1979), brought a more eclectic sound, mixing world music influences with Bowie’s continued interest in experimentation. Lyrically, the album explored themes of displacement, travel, and alienation, with Bowie moving further away from the grand narratives of his earlier work. While still engaging with electronic sounds and avant-garde approaches, Lodger had a more accessible feel compared to the previous two albums, signaling that Bowie was ready to emerge from the shadows of introspection.

An Experimental Period

During this era, Bowie’s persona was less outwardly theatrical, but it reflected a profound transformation. Rather than using a character to convey his artistic ideas, Bowie himself became the canvas. His appearance during this time was understated, often dressed in simple clothes, with none of the flamboyant costumes or makeup that had defined Ziggy Stardust or Aladdin Sane. This shift allowed Bowie to focus more on the music and on exploring new artistic territories, free from the burden of embodying a larger-than-life persona. The Bowie of the Berlin Era was an experimenter, someone unafraid to strip everything down and start over, both personally and artistically.

The influence of Berlin’s music scene on Bowie during this period cannot be overstated. The city’s industrial soundscapes, its sense of artistic freedom, and the palpable tension of its geopolitical situation (being divided by the Wall) seeped into the music Bowie created. His collaborations with Brian Eno pushed him further into the realms of electronic music and avant-garde composition, helping him craft a sound that was far ahead of its time. Bowie’s experimentation during the Berlin Era laid the groundwork for much of the post-punk, new wave, and electronic music that would emerge in the 1980s.

Pierrot and the Return to Theatricality (1980)

The Clown of Melancholy

In 1980, after the introspective and experimental period of the Berlin Era, David Bowie returned to a more theatrical persona with the release of Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps). This time, he embodied Pierrot, the sad, tragic clown of French commedia dell’arte, to represent a new phase of his career. Unlike the alien or dystopian characters of his past, the Pierrot figure reflected Bowie’s desire to confront his own vulnerability and mortality while still playing with themes of artistic reinvention. The return to a heightened sense of visual style and performance marked a new chapter in Bowie’s journey—a combination of avant-garde theater and self-reflection.

Scary Monsters

Pierrot, as seen on the album’s cover and in the music video for “Ashes to Ashes,” is a figure of melancholy and nostalgia. Dressed in a billowing, white clown costume with dramatic makeup, Bowie’s Pierrot presents an image of fragility, suggesting a figure haunted by the past. This was no coincidence—Scary Monsters was a deeply personal album for Bowie, one where he seemed to confront both the successes and failures of his career up to that point. The Pierrot character, with its association with sadness and loss, was a perfect metaphor for this phase of Bowie’s life, as he looked back on his past personas with a sense of distance and detachment.

The song “Ashes to Ashes”, one of the standout tracks on the album, is a prime example of how Bowie used the Pierrot figure to reflect vulnerability. In the song, Bowie revisits the character of Major Tom, the astronaut from his 1969 hit “Space Oddity.” However, this time, Major Tom is no longer a heroic explorer—he’s a broken figure, “strung out in heaven’s high” and lost in space, a metaphor for addiction and alienation.

The music video for “Ashes to Ashes,” which became an iconic visual moment in the history of music videos, features Bowie as Pierrot, wandering through a surreal, dreamlike landscape. The video’s stark colors and avant-garde imagery helped redefine what could be done with the music video format, blending art-house aesthetics with pop culture in a way that felt both accessible and experimental.

The Concept

Pierrot’s clownish vulnerability contrasts with Bowie’s previous personas, who were often otherworldly or detached from emotion. With Pierrot, Bowie embraced the idea of the wounded artist, grappling with the weight of his own mythology. The character evokes a sense of nostalgia for the personas that had come before—Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke—but also signals that Bowie was ready to move forward, leaving these identities behind as he reinvented himself once again.

At the same time, the use of avant-garde theater in Pierrot’s portrayal gave Bowie a new artistic framework. The character allowed Bowie to experiment with the blending of high art and pop culture, using the figure of the sad clown to comment on the complexities of fame, identity, and reinvention. Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps), while musically diverse with its mix of post-punk, new wave, and art rock, also reflected a thematic sense of unease and dislocation, mirroring Pierrot’s internal conflicts.

This era marked Bowie’s return to theatricality, but it was a more reflective, self-aware version of the artist than the brashness of Ziggy or the coolness of the Thin White Duke. The Pierrot persona allowed Bowie to navigate the complicated relationship between his past and his present. By using the image of the sad clown, Bowie acknowledged the melancholic nature of constant reinvention—the idea that to move forward, he had to let go of his previous selves, even as they haunted him.

Let’s Dance and the Pop Star Persona (1983-1987)

Bowie, the Global Icon

By the early 1980s, David Bowie had already spent more than a decade reinventing himself, transitioning from avant-garde outsider to one of the most influential figures in rock music. Yet, with the release of Let’s Dance in 1983, Bowie made one of his most radical shifts yet: he embraced the role of a mainstream pop star, stepping into the spotlight as a global icon.

For an artist who had long played with the boundaries of identity and genre, this period marked a decisive move toward accessibility, making him a household name and propelling him to levels of fame he had never reached before. It also, however, led to creative struggles that would weigh heavily on him in the years to come.

Let’s Dance

Let’s Dance, produced by Nile Rodgers of Chic, was the album that cemented Bowie’s place in the pantheon of 1980s pop superstars. The album’s title track, with its infectious rhythm, sleek production, and polished, radio-friendly sound, became an instant hit, dominating the charts worldwide. It was Bowie’s commercial high-water mark, blending the danceable grooves of funk and disco with a pop sensibility that appealed to a far broader audience than his more experimental works. Hits like “China Girl” and “Modern Love” followed suit, showcasing Bowie’s ability to craft songs that were both artistically sophisticated and accessible enough to fit into the emerging MTV-driven music landscape.

This period saw Bowie shift away from the avant-garde personas that had defined his earlier career. Gone were the androgynous aliens and dystopian rebels. Instead, Bowie’s new image was one of an impeccably dressed, stylish, and charismatic global pop icon. His persona during this time was refined, sleek, and confident—tailored to the demands of a mass-market audience.

Embracing Pop

Bowie’s collaboration with Nile Rodgers was key in shaping this sound and image, with Rodgers helping Bowie to strip down his more experimental tendencies in favor of tight, groove-heavy compositions that would play well on radio and in clubs. The result was a sound that merged Bowie’s artistic flair with Rodgers’ expertise in creating crossover hits, drawing on the influences of funk, soul, and rhythm and blues, but packaged in a way that was irresistibly pop.

At the heart of this transformation was MTV, the music video network that exploded in popularity in the early 1980s. Bowie, always ahead of the curve, recognized the importance of the visual medium in shaping his pop persona. The music video for “Let’s Dance,” with its vibrant visuals and commentary on race and cultural identity, became iconic, amplifying Bowie’s global reach and solidifying his status as a visual innovator in the MTV age. In an era when image was becoming as important as sound, Bowie’s stylish yet approachable new look made him a natural fit for the pop landscape of the 1980s.

Mainstream Success

Bowie’s new pop star persona was not just about music and image—it was about global superstardom. The success of Let’s Dance transformed Bowie into one of the biggest names in the world, with sold-out stadium tours and a presence that transcended music, influencing fashion, art, and film. His collaboration with Nile Rodgers was pivotal in shaping this era, as Rodgers helped Bowie channel his creative energy into a sound that was radio-friendly without losing its artistic edge. This partnership demonstrated Bowie’s ability to adapt to changing musical landscapes, proving that he could still reinvent himself in ways that resonated with the zeitgeist.

However, this period of mainstream success came at a cost. As Bowie embraced the role of a pop icon, he began to experience creative burnout. The pressure to maintain his newfound commercial success, along with the constraints of creating more conventional pop music, began to wear on him. After years of pushing the boundaries of music and performance with personas like Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke, Bowie found himself constrained by the expectations of the pop market.

Limitations

Albums like Tonight (1984) and Never Let Me Down (1987) failed to capture the same magic as Let’s Dance, and Bowie himself later admitted to feeling artistically unfulfilled during this period. He struggled with the limitations of his pop star persona, sensing that the image he had crafted had taken on a life of its own, one that no longer aligned with his deeper artistic impulses.

The Let’s Dance era was a double-edged sword for Bowie. On one hand, it allowed him to reach a broader audience than ever before, solidifying his place as a global pop icon and bringing his music to millions of new fans. On the other hand, it led to a period of creative stagnation, as Bowie grappled with the tension between commercial success and artistic integrity. While Let’s Dance and its accompanying tours brought him unparalleled fame, it also marked a moment when Bowie began to feel disconnected from the fearless experimentation that had defined so much of his earlier work.

The Late Bowie: Earthling, Heathen, and The Elder Statesman (1990s-2016)

Bowie in the Digital Age

By the 1990s, David Bowie had already spent decades reinventing himself, but as the world transitioned into the digital age, so did Bowie. Rather than resting on his legendary status, he embraced the rapidly changing musical landscape, experimenting with genres like industrial, drum and bass, and electronic music. During this period, Bowie took on the persona of a digital-age prophet—an artist who not only explored futuristic sounds but also engaged deeply with the rise of the internet and digital culture. At the same time, he positioned himself as a nostalgic outsider, reflecting on the past while pushing forward into new sonic territory.

Earthling

In the mid-1990s, Bowie released Earthling (1997), an album that encapsulated this era of experimentation. Drawing heavily from drum and bass, techno, and industrial music, Earthling showcased a version of Bowie that was fully immersed in the digital revolution. Songs like “Little Wonder” and “I’m Afraid of Americans” were energetic and abrasive, marked by frenetic breakbeats and distorted guitars. With Earthling, Bowie adopted the aesthetic of a cyberpunk futurist, donning colorful, edgy outfits and interacting with the fast-evolving world of the internet. His engagement with cutting-edge music genres reflected not just a desire to stay relevant but to actively participate in shaping the sounds of the future.

Heathen

Yet, even as Bowie explored new musical horizons, he was also grappling with his own legacy. In albums like Heathen (2002), Bowie struck a delicate balance between modern innovation and personal reflection. Heathen saw Bowie returning to more introspective themes, blending nostalgia with futurism. The album was more subdued than Earthling, featuring rich, atmospheric soundscapes and exploring themes of existential anxiety, spirituality, and the passage of time.

Tracks like “Sunday” and “Slow Burn” reflect Bowie’s contemplations on aging and uncertainty in a post-9/11 world, where his voice became a soothing yet questioning presence, signaling both reflection and a sense of continued reinvention. In this period, Bowie became the elder statesman of rock, a figure who had lived through decades of change but was still in conversation with the modern world.

Throughout the 2000s, Bowie’s persona was increasingly defined by a sense of self-awareness about his aging and mortality, but his approach was far from nostalgic in the typical sense. He was continually evolving, even as he became more selective about his public appearances and music releases. In his later years, Bowie stepped back from the limelight, living a relatively private life in New York, but whenever he resurfaced, it was clear that his mind remained sharp and his creativity undiminished. He used his “outsider” status as an artist who had already achieved legendary status to challenge norms quietly, becoming more enigmatic and letting the music speak for itself.

Blackstar

Bowie’s ultimate reflection on mortality and legacy came with his final album, Blackstar (2016), released just days before his death. The persona Bowie inhabited on Blackstar was his most poignant yet—an artist confronting his own mortality with a sense of grace, mystery, and profound creativity. Blackstar was sonically adventurous, blending jazz, experimental rock, and haunting electronic textures. Songs like the title track and “Lazarus” are filled with cryptic references to death, the afterlife, and Bowie’s acceptance of his inevitable fate. The lyrics of “Lazarus” (“Look up here, I’m in heaven”) are chilling in their directness, as Bowie used the music to communicate with his audience one last time, turning his own death into a piece of art.

In the Blackstar era, Bowie’s persona was defined by an elegant contemplation of death and legacy. Bowie used this final chapter to reflect on his past selves while crafting something entirely new—proving once again that even in the face of his own mortality, he was still an innovator. The visuals for Blackstar and the music video for “Lazarus” saw Bowie blending old themes (the spaceman, the mysterious artist) with stark imagery of death, such as the iconic image of him lying on a hospital bed, blindfolded and frail. Despite the album’s darkness, it was also a final act of reinvention, with Bowie using his death as the ultimate artistic statement.

Closing Thoughts

David Bowie’s personas are the ultimate embodiment of continuous reinvention—an artist whose identity was never static, always evolving in response to both the changing cultural landscape and his own creative impulses. From the alien glam rock of Ziggy Stardust to the haunting reflections of Blackstar, Bowie’s chameleon-like transformations were not just about aesthetics or gimmicks. They were deeply connected to his exploration of music, art, and the human condition.

Bowie used each persona to challenge conventional notions of identity, creating a series of avatars that allowed him to break free from the constraints of any single genre, image, or expectation. In doing so, he redefined what it meant to be a pop star, turning himself into a living work of art.