Released in 1970, The Man Who Sold the World marked a turning point in David Bowie’s early career. Coming off the lighter, more folk-inflected tones of his 1969 self-titled album, which included the breakout single “Space Oddity,” Bowie took a sharp left turn. This third studio album dives into darker themes and embraces a heavier rock sound, setting it apart from his previous work. It was his first real exploration of hard rock and proto-metal, blending complex lyrics with ominous, guitar-driven arrangements.

The album emerged during a time of significant change in the rock world. Acts like Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath were pushing the boundaries of what rock could be, and Bowie joined the conversation with a sound that was both theatrical and foreboding. While not yet the glam rock icon he would become, Bowie used The Man Who Sold the World to test the limits of his musical identity.

Artistically, the album reflects Bowie’s growing interest in themes of madness, identity, and the surreal. These ideas were not new to him, but here they took on a sharper edge. According to various interviews over the years, Bowie used the album as a mirror for the chaos he observed both in society and within himself. It is an album that confronts fear and transformation head-on, laying the groundwork for the personas and sonic shifts that would define the rest of his career.

Sonic Exploration

The Man Who Sold the World is where David Bowie’s sound grew teeth. The production, handled by Tony Visconti, trades the polish of pop for something raw and muscular. It is not lo-fi in the traditional sense, but it leans into a heavier, almost menacing tone. The album feels thick with atmosphere, thanks to dense layers of electric guitar and a rhythm section that pounds more than it pulses. This weight in the production matches the lyrical descent into psychological unease and fractured identity.

Musical Arrangements

At the heart of the album’s sound is Mick Ronson, whose guitar work shapes much of the album’s character. His riffs on tracks like “She Shook Me Cold” and “Width of a Circle” push into the territory of early metal, with fuzz-laden distortion and long instrumental stretches that feel almost improvised. This was not the typical structure of pop rock at the time. Instead, the arrangements let songs breathe and sprawl, giving the listener room to wander through Bowie’s cryptic lyrics and the band’s sonic explorations.

Visconti’s bass playing also deserves mention. His lines are active and melodic, not content to simply anchor the songs. The interplay between bass and guitar creates a sense of movement even in the album’s darker moments. Meanwhile, the drums, played by Woody Woodmansey, are tight but aggressive, driving the energy forward without ever feeling showy.

Vocally, Bowie experiments with tone and character. He shifts between hushed, almost spoken-word delivery and bold theatrical flair. His voice serves as another instrument, adapting to the mood of each track rather than sticking to one vocal style. This fluidity adds to the sense that the album is a psychological journey rather than a collection of singles.

Genre Elements

Genre-wise, the album plants its feet in hard rock and proto-metal, but it also nods to psychedelic rock, blues, and even early glam. The sound is not quite settled. Instead, it feels like Bowie is testing different styles to see what fits, which adds to the album’s restless energy. While not as genre-bending as his later work, the seeds of that experimentation are here.

Lyrical Analysis

The lyrics of The Man Who Sold the World reach deep into the shadows of the human psyche. Bowie uses the album to explore themes of identity, mental illness, and alienation. These are not just passing references. They form the backbone of the record. From the opening moments of “Width of a Circle,” where Bowie blurs the line between spiritual transformation and psychological breakdown, the listener is pulled into a world that feels unstable and questioning.

One of the most striking motifs on the album is the duality of self. This is most clearly seen in the title track, where the narrator meets a version of himself he thought had long disappeared. It’s a haunting idea — confronting the parts of ourselves that we pretend don’t exist. Bowie doesn’t give easy answers. Instead, he leaves space for ambiguity, which adds to the emotional weight of the lyrics.

Lyrical Depth

The writing is complex, but not in a way that feels distant. Bowie uses vivid images and strange characters to tell stories that reflect deeper anxieties. In “All the Madmen,” for example, he paints a world where madness is not a flaw but a form of truth. The lyrics challenge the idea of what is sane and what is not. The words are poetic, but also unsettling. They resist straightforward interpretation, inviting the listener to sit with uncertainty.

Even the more grounded songs carry a sense of something slipping out of control. In “Running Gun Blues,” the narrative voice takes on a disturbing persona — a soldier intoxicated by violence. It’s a bold move that adds a layer of social commentary without being preachy. Bowie doesn’t moralize. He observes, dramatizes, and lets the discomfort linger.

Emotional Impact

The emotional impact of the lyrics is lasting. They don’t offer comfort or resolution. Instead, they open up questions about who we are and what lies beneath the surface. There is sadness here, but also curiosity and defiance. Bowie doesn’t wallow in despair. He studies it, gives it a voice, and dares the listener to do the same.

Cohesion and Flow

The Man Who Sold the World unfolds less like a straightforward story and more like a series of fractured mirrors, each reflecting a different angle of the same psychological unease. Still, the album manages to maintain a strong internal logic. The track progression feels intentional, moving from moments of explosive energy to quieter, more introspective spaces in a way that mirrors the emotional currents running through the lyrics.

Track Progression

The opening track, “The Width of a Circle,” sets the stage with a sprawling, multi-part structure. It introduces many of the album’s key elements — heavy guitar work, lyrical ambiguity, and a descent into internal conflict. From there, the album moves through tracks like “All the Madmen” and “After All,” each deepening the sense of instability. These songs don’t just follow one another; they interact, creating a dialogue that builds tension and complexity.

There is no strict narrative thread, but a clear emotional progression takes shape. As the album moves forward, the tone shifts from theatrical confrontation to eerie reflection. “Saviour Machine” and “She Shook Me Cold” bring bursts of intensity, while the title track feels almost like a dream — soft in sound but sharp in message. The closing track, “The Supermen,” ends things on an apocalyptic note, suggesting that the journey through self and society has not offered peace but a kind of resigned awe.

Thematic Consistency

Thematically, the album holds together with impressive consistency. Whether Bowie is singing about madness, identity, or dystopian futures, the mood remains coherent. There are no jarring stylistic jumps or emotional detours that break the atmosphere. Even when the genre edges shift — from hard rock to psychedelic or gothic undertones — they feel like part of the same fabric. This unity gives the album a sense of purpose. It is not just a collection of songs, but a single artistic statement.

Standout Tracks and Moments

Several tracks on The Man Who Sold the World rise to the surface as defining moments in Bowie’s early evolution, each offering a glimpse of the bold artist he was becoming.

The Man Who Sold the World

The title track, “The Man Who Sold the World,” is perhaps the album’s most iconic song. Its haunting melody and cryptic lyrics capture the album’s central theme of duality and internal conflict. The subdued, spiraling guitar riff creates a sense of eerie calm, which contrasts with the unsettling narrative of identity loss. The song’s power lies in its restraint. It does not shout; it lingers, leaving the listener with questions that stick long after the track ends.

All the Madmen

Another standout is “All the Madmen.” With its layered vocals and theatrical delivery, the song dives deep into the theme of mental illness. The lyrics, inspired in part by Bowie’s own family history, carry emotional weight. The contrast between the song’s almost whimsical tone and its dark subject matter adds complexity. It’s a track that manages to be both playful and profound.

She Shook Me Cold

“She Shook Me Cold” showcases the album’s heaviest rock influence. It’s a raw, guitar-driven track that leans into the power of the band. Mick Ronson’s playing here is relentless, delivering one of the album’s most memorable solos. Though the lyrics are more direct and rooted in blues-rock tradition, the song stands out for its sheer energy and sonic intensity.

After All

A subtler but equally powerful moment comes in “After All.” The song slows the pace and introduces a creepy, carousel-like rhythm that feels like a descent into a dream. Bowie’s vocal delivery is almost whispered at times, drawing the listener in close. The line “Live till your rebirth and do what you will” is both poetic and philosophical, capturing the album’s fascination with transformation.

The Width of a Circle

Then there’s “The Width of a Circle,” a bold opener that clocks in at over eight minutes. It shifts gears multiple times, moving from spiritual pondering to sexual revelation, all underscored by aggressive instrumentation. It sets the tone for the album’s ambition and restlessness. The breakdown around the midpoint, where the tempo drops and Ronson’s guitar takes center stage, is one of the record’s most thrilling musical passages.

Artistic Contribution and Innovation

At the time of its release, The Man Who Sold the World didn’t make a huge commercial splash. But in hindsight, it stands as one of the most crucial turning points in David Bowie’s career — and in the evolution of rock music. It was not just another early ’70s rock album. It was a bold step into a darker, more introspective sound that helped reshape the boundaries of what rock could explore.

Within the broader landscape of the era, the album fits alongside the rise of heavy rock and early metal. Bands like Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin were already laying the groundwork for those genres, and Bowie’s contribution here feels like an artful companion. He didn’t just adopt the heavy guitar sound — he filtered it through a lens of psychological unease and theatrical flair. That combination gave the album a distinct place in the rock canon. It wasn’t pure metal, nor was it traditional singer-songwriter fare. It occupied a space in between, and that made it feel fresh.

Themes

What makes the album innovative is its fusion of raw sound with complex, literary themes. Few artists at the time were willing to dive so deeply into questions of identity, mental instability, and societal decay with such directness. Bowie’s lyrical ambition paired with the aggressive musical backdrop was unusual. He wasn’t offering comfort. He was holding up a mirror and asking the listener to look closer.

Production

Production-wise, Tony Visconti helped shape a sound that was heavy without being chaotic. The clarity of the instrumentation, especially given the layered guitars and dense arrangements, allowed each track to maintain its own mood. That attention to detail would later become a hallmark of Bowie’s work, but here it was still in its formative stage — bold, raw, and deeply atmospheric.

Glam Rock Beginnings

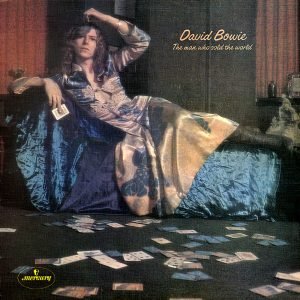

Perhaps most importantly, The Man Who Sold the World helped lay the foundation for glam rock. It hinted at the theatricality Bowie would soon fully embrace, while also carving out space for gender ambiguity and nonconformity in rock. His appearance on the album cover — wearing a dress and reclining like a Renaissance muse — was itself a provocation. It signaled that Bowie was not just interested in sound, but in identity as performance. That message would echo loudly through his later personas, from Ziggy Stardust to the Thin White Duke.

Closing Thoughts

The Man Who Sold the World is not David Bowie’s most accessible album, but it may be one of his most important. It captures a moment of artistic transformation, where Bowie began shedding the conventions of pop and stepping into something far more daring. The album’s strengths lie in its fearless sonic experimentation, its poetic yet unsettling lyrics, and its willingness to confront themes that most artists of the time avoided.

It is not without its flaws. Some tracks, like “She Shook Me Cold,” can feel more like exercises in style than fully realized songs. The flow of the album, while cohesive in tone, lacks the polish and precision of Bowie’s later masterpieces. At times, the production leans so heavily into its dark atmosphere that it risks alienating more casual listeners.

But these imperfections are part of what make the album feel vital. It is raw, restless, and unapologetically complex. For listeners willing to dig beneath the surface, it offers rewards that extend far beyond its initial impact. It invites repeat listens, not because it is easy to love, but because it refuses to be pinned down.

As a part of Bowie’s discography, this album marks the true beginning of his artistic identity. It sets the stage for the characters, sounds, and provocations that would follow. It is a blueprint for everything that made him a cultural icon.

Official Rating: 8/10

This rating reflects the album’s bold vision, its genre-defying sound, and its deep influence on both Bowie’s career and the wider rock landscape. While it may not reach the polished heights of his later work, it stands as a landmark of artistic risk — and one that still resonates decades later.