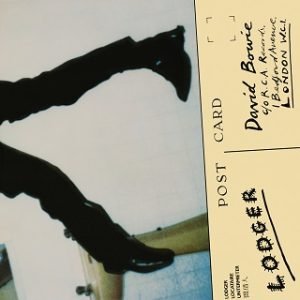

David Bowie’s Lodger, released in May 1979, stands as the final entry in his groundbreaking “Berlin Trilogy,” a series of albums co-created with producer Brian Eno that explored sonic innovation and fractured narratives. While Lodger shares a spiritual kinship with its predecessors, Low (1977) and “Heroes” (1977), it ventures into a different creative space, marking a subtle shift in both sound and vision. Where Low and “Heroes” were dominated by ambient experimentation and instrumental passages, Lodger returns Bowie to a more traditional song structure—but with a twist. It combines the avant-garde sensibilities of the trilogy with more accessible, albeit skewed, pop forms.

In terms of the broader music landscape, Lodger emerges at a time when post-punk and New Wave were beginning to crystallize, genres heavily influenced by Bowie’s own 1970s reinventions. The album feels less alien than the earlier trilogy entries, yet more chaotic in its approach, marrying global influences with fragmented rhythms and dense lyrical themes. Its global outlook—pulling in sonic elements from Turkish and African music—hints at Bowie’s growing fascination with cultural cross-pollination, prefiguring his more explicit world music explorations in the ’80s.

Artistic Intentions

As for Bowie’s artistic intentions, Lodger can be seen as a critique of Western culture’s disconnection, both geographically and spiritually. While not as overtly dystopian as Diamond Dogs (1974), it grapples with themes of displacement, exile, and the fraying edges of identity. In interviews around the time of its release, Bowie remarked that he saw Lodger as a kind of “travelogue” without a clear destination—an observation that captures the album’s restlessness. Rather than providing clear answers or cohesive narratives, Lodger is a snapshot of chaos, with Bowie acting as both tourist and commentator, wandering through a world where borders, both political and personal, are constantly shifting.

In the context of his discography, Lodger is often seen as the album where Bowie reined in the more abstract tendencies of his Berlin period. It’s more direct, yet still radically experimental—an album where the familiar pop song is deconstructed, fragmented, and pieced back together in unexpected ways. Through this record, Bowie pushes back against the notion of belonging or permanence, offering instead a sonic landscape that refuses to be pinned down, much like the artist himself.

Sonic Exploration

Production Quality

The production of Lodger straddles the line between art-rock experimentation and pop accessibility, creating an album that feels both disjointed and intricately layered. While the earlier two installments of Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy (Low and “Heroes”) embraced a stark, atmospheric production that left ample space for mood-setting and ambiguity, Lodger takes a different route. The production is denser, messier, almost claustrophobic at times, which feels intentional, as if Bowie and co-producer Brian Eno wanted to reflect the fractured and nomadic spirit of the album’s themes. Tony Visconti’s engineering captures this tension: the record is neither pristine nor entirely gritty, but it leans into a certain rawness, particularly through its unpolished, almost live-feeling vocal takes and unpredictable sonic textures.

Notably, Lodger opts out of the long, ambient instrumental sections that marked the earlier Berlin Trilogy records, focusing instead on tightly constructed, but still avant-garde, pop songs. The album’s production creates a sense of immediacy and urgency, with Bowie’s voice often cutting through a kaleidoscope of sounds. Tracks like “African Night Flight” and “Red Sails” are brimming with layers of sounds that feel urgent and chaotic, lending to the feeling of disorientation that runs through the album. The production, while not conventionally “crisp,” is purposefully scattered, reinforcing the album’s thematic concerns of fragmentation, travel, and alienation.

Musical Arrangements

The arrangements on Lodger are daring, melding a wide array of cultural and sonic influences in ways that can feel simultaneously cohesive and chaotic. Bowie and Eno continue their trademark sound manipulation, playing with structure and texture, but the result here is less polished and more urgent. The album’s instrumentation—ranging from fractured rock riffs to non-Western scales—helps create a fluid, almost borderless musical landscape. Carlos Alomar’s guitar work shifts between jagged, almost punk-like stabs (as in “Look Back in Anger”) and exotic, serpentine melodies (“Yassassin”), while Dennis Davis’ drumming—irregular and unpredictable—provides a foundation that often feels unstable, as if it’s constantly shifting underneath the listener’s feet.

The use of unconventional scales and rhythms is particularly notable. On “Yassassin,” for instance, the Middle Eastern-inspired melody rides atop a reggae-inflected beat, creating a hybrid sound that’s difficult to pin to one genre. In “African Night Flight,” frenetic, almost chant-like vocals are underpinned by tribal percussive elements, further blurring the lines between genres and geographies. These kinds of arrangements, with their global reach and eclectic nature, make Lodger a bold statement on cultural fusion, but also one that reflects a sense of instability. Nothing feels fully at rest.

Vocally, Bowie is unrestrained, sometimes singing with an almost conversational looseness, at other times veering into manic, warbled delivery. His vocals on tracks like “DJ” and “Boys Keep Swinging” are particularly dynamic, moving from wry detachment to moments of raw, unfiltered energy. This vocal unpredictability adds another layer to the album’s theme of displacement and disorientation, as Bowie seems to be adopting different personas and emotional registers from track to track.

Genre Elements

Musically, Lodger is a genre-hopping journey. The album primarily rests within the realms of art rock and post-punk, but it frequently veers into unexpected directions. It pulls influences from krautrock, New Wave, world music, and even early hints of punk, blending them into a soundscape that is as diverse as it is disjointed. For example, “African Night Flight” blends experimental rock with African-inspired rhythms, while “Move On” borrows heavily from the melody of Bowie’s earlier hit “All the Young Dudes” but drenches it in an almost cinematic, nomadic feel, emphasizing the album’s wandering ethos.

What makes Lodger particularly striking is how it refracts these genre influences through Bowie’s avant-garde lens. Lodger doesn’t conform to the rising New Wave sound of the late ’70s, though it shares some sonic similarities in its use of synthesizers and angular guitar work. Nor does it settle comfortably into punk’s stripped-down ethos, despite moments of punk-ish energy. Instead, it exists in a liminal space, blending genres in ways that feel fresh and challenging even today. The reggae groove on “Yassassin,” the fractured funk of “DJ,” the dissonant punk of “Repetition”—each song pulls from distinct musical traditions but never stays long enough to be pinned down.

In this sense, Lodger is less about genre conformity and more about genre deconstruction. Bowie and Eno take familiar sounds and warp them, creating an album that feels exploratory and restless, much like the nomadic characters Bowie portrays in his lyrics. The album’s refusal to stay tethered to one musical style enhances its sense of transience and cultural dislocation, embodying the very themes of travel, exile, and identity that are at its core.

Lyrical Analysis

Themes and Messages

At its core, Lodger explores themes of displacement, cultural dislocation, and identity. David Bowie positions himself as a wandering observer, sometimes empathetic, sometimes detached, navigating a world in flux. This nomadic quality is reflected in both the literal sense of travel and a deeper, existential search for belonging. The lyrics often reference movement and journey, whether it’s the physical act of travel or the metaphorical passage through life’s uncertainties.

One of the album’s central themes is alienation, particularly from modern Western culture. In songs like “Fantastic Voyage” and “African Night Flight,” Bowie examines the anxiety of a fractured world, where borders—both physical and emotional—are dissolving. “Move On,” another travel-centric track, explicitly deals with the transience of life, framing travel not as a joyous adventure but as a continual act of running without a true destination. Meanwhile, “Yassassin” and “Red Sails” evoke images of escape and cultural collision, exploring a sense of being caught between worlds, never quite at home.

A recurring motif throughout Lodger is that of exile and detachment. On “Boys Keep Swinging,” for example, Bowie seems to critique conventional masculinity through satirical lyrics about privilege and gender roles, hinting at the societal expectations that restrict identity. In “Repetition,” he delves into the darkness of domestic violence, using stark, minimal language to depict the mindless cycle of abuse. These themes collectively form a broader critique of societal norms, capitalism, and the shallow comforts of modernity.

Lyrical Depth

The lyrics on Lodger are often abstract and impressionistic, much like the music itself. Bowie moves away from straightforward narratives, opting instead for fragmented storytelling that mirrors the album’s restless tone. There are moments of sharp clarity—such as the bluntly critical “Repetition”—but much of Lodger invites open interpretation. Songs like “African Night Flight” are cryptic, with frantic vocal delivery that reads almost like stream-of-consciousness, adding to the song’s chaotic, disjointed feel. It’s less about the specific meaning of the words and more about the atmosphere they create, making the listener feel as though they are experiencing Bowie’s fragmented worldview along with him.

Bowie uses surrealist imagery throughout the album, making the lyrics feel poetic even when they appear nonsensical on the surface. Take, for instance, the line “Back to the funny farm” in “Fantastic Voyage,” which evokes both the mental and emotional instability of a collapsing world. In “Red Sails,” Bowie sings about sailing through unknown seas, offering vivid but dreamlike visuals that convey a sense of adventure with an undercurrent of anxiety. The lyrics are often oblique, leaving space for multiple interpretations. This complexity adds layers to the album, allowing each listener to draw their own conclusions about the album’s messages.

Though abstract, the lyrics on Lodger are not without purpose. Bowie’s frequent shifts between cryptic phrases and direct statements challenge the listener to consider deeper meanings. The lines in “Fantastic Voyage” about nuclear war—“And the wrong words make you listen / In this criminal world”—might be cloaked in vague imagery, but they speak to the urgent fears of the Cold War era. Bowie’s ability to weave political and existential concerns into surrealist landscapes speaks to his skill as a lyricist, creating poetry out of chaos.

Emotional Impact

The emotional range of Lodger is as varied as its musical and lyrical content, evoking feelings of unease, melancholy, and ironic detachment. There is a persistent tension running through the album, driven by Bowie’s meditations on displacement and existential doubt. Tracks like “Look Back in Anger” convey a mounting sense of frustration and helplessness, as Bowie’s lyrics examine a protagonist overwhelmed by guilt and despair. The rawness of the vocal delivery, combined with the grim lyrical tone, makes this one of the album’s most emotionally resonant tracks.

“Repetition” stands out for its brutal emotional impact. Bowie’s detached, almost clinical description of domestic abuse is chilling in its lack of ornamentation: “He’s going to the kitchen / To get things to eat / He don’t care about me.” The starkness of the language heightens the horror, making the emotional blow hit harder. Unlike many of the album’s more abstract lyrics, “Repetition” leaves no room for ambiguity, presenting a haunting portrait of violence without resolution.

On the other end of the emotional spectrum is “Boys Keep Swinging,” where Bowie adopts a more sardonic tone. The lyrics, which at first glance might seem celebratory of male privilege, are laced with irony and sarcasm, exposing the shallow triumphs of gender roles. This playfulness offers a momentary reprieve from the heavier themes of the album, but it’s a cynical joy—a joy that feels hollow in the face of the deeper disillusionment explored elsewhere.

Cohesion and Flow

Track Progression

One of the most intriguing aspects of Lodger is how its tracks flow—or more accurately, don’t flow—into one another. The album seems to intentionally defy traditional notions of smooth progression. Rather than offering a clear, linear emotional or narrative arc, Lodger presents itself as a series of vignettes, each with its own distinct atmosphere. This fragmented approach reflects the album’s themes of dislocation and restlessness. There’s a sense of intentional dissonance as the listener is pulled from one setting to the next without much warning, as if the album is mimicking the unpredictable nature of travel itself.

The opening track, “Fantastic Voyage,” is gentle and contemplative, easing the listener into the album with its melancholy reflection on global tensions. But this reflective tone is immediately disrupted by the frenetic “African Night Flight,” a cacophonous barrage of jittery vocals and percussive chaos. The sudden shift in energy between these two tracks is startling, and this jarring transition sets the tone for much of the album’s progression. Rather than allowing the listener to settle into a particular mood or rhythm, Bowie and Eno seem intent on keeping things unsettled, mirroring the fragmented state of mind the album conveys.

That said, while the tracks may not flow smoothly in a traditional sense, there is a sense of logic to their arrangement. Songs like “DJ” and “Look Back in Anger” both possess an anxious, frenetic energy that ties them together, while the latter half of the album, starting with “Red Sails,” takes a more exotic, globe-trotting turn, pulling the listener into Bowie’s vision of cultural displacement. The album closes with the haunting “Red Money,” a reworking of Iggy Pop’s “Sister Midnight,” which brings the album full circle by revisiting earlier themes of alienation and fractured identity.

In short, the track progression in Lodger doesn’t follow a clear narrative path, but this lack of cohesion feels purposeful. It enhances the album’s central theme of constant movement and instability, making the listener feel as though they are being transported from one location to the next without any time to fully adjust.

Thematic Consistency

Though the album’s track transitions can be abrupt, the thematic consistency across Lodger is impressively maintained. Every song, in some way, touches on ideas of displacement, travel, cultural fusion, or the alienation of modern life. The sense of wandering, whether physical or existential, is present from the beginning with “Fantastic Voyage” and carries through to the end with “Red Money.” Bowie’s lyrical motifs of being in transit, of not belonging, and of questioning identity provide a throughline that keeps the album grounded, despite its sonic unpredictability.

Musically, Lodger is equally consistent in its thematic exploration. The blending of genres—ranging from art rock to New Wave, with touches of world music—creates a soundscape that feels as borderless as the album’s lyrical content. Even when the style shifts dramatically from one track to the next, the overarching sense of cultural collision remains intact. For instance, “Yassassin” incorporates Turkish folk elements, while “Red Sails” leans into krautrock influences, yet both songs contribute to the album’s broader exploration of cross-cultural experimentation and the feeling of being out of place.

Emotionally, the album also retains a cohesive sense of uncertainty and tension. Whether Bowie is critiquing modern masculinity in “Boys Keep Swinging” or depicting the monotony of domestic abuse in “Repetition,” there’s an undercurrent of dissatisfaction and alienation that runs through nearly every track. The few moments of joy or levity, like the ironic cheer of “Boys Keep Swinging,” are quickly undercut by the darker, more cynical turns of the album.

While the album’s eclectic sonic palette might at first glance seem disjointed, the thematic consistency running through Lodger ties everything together, making it a cohesive work despite its surface-level unpredictability. Bowie and Eno’s willingness to jump between styles and moods reflects the fractured, nomadic experience the album seeks to convey. In this sense, the occasional jarring shifts in sound only serve to strengthen the album’s overarching vision of instability and transience, making Lodger a masterclass in controlled chaos.

Standout Tracks and Moments

Highlight Key Tracks

While Lodger is often praised for its overall eclecticism, a few tracks rise to the surface as particularly significant in terms of artistic merit, innovation, and emotional impact. These songs exemplify the album’s chaotic energy and thematic depth, while also showcasing David Bowie’s unique ability to craft memorable, genre-defying music.

“Boys Keep Swinging”

“Boys Keep Swinging” stands out as one of Lodger‘s most accessible and subversive tracks. With its swaggering, glam-rock energy, the song feels like a callback to Bowie’s earlier work, but its ironic take on masculinity sets it apart. Lyrically, Bowie plays with themes of male privilege, delivering tongue-in-cheek lines like “When you’re a boy / You can wear a uniform” with an exaggerated bravado that borders on satire. Musically, it’s a burst of joyful simplicity, propelled by a driving rhythm and brash guitar riffs from Carlos Alomar. The punkish, raw energy combined with Bowie’s playful delivery makes this track a standout for both its catchiness and its biting critique of gender norms.

“DJ”

“DJ” captures the alienation and detachment that permeate Lodger. It’s a fascinating critique of modern fame and cultural obsession with celebrity, told through the perspective of a disillusioned disc jockey. Musically, the track is built around a funk-inflected groove, with angular guitars and a jittery beat that reflect the fractured psyche of the protagonist. Bowie’s delivery is sarcastic and almost deadpan, as he sings, “I am a DJ, I am what I play,” evoking the existential emptiness that comes from blending personal identity with public persona. The repeated guitar riffs, courtesy of Adrian Belew, are jagged and discordant, matching the song’s theme of disconnection. “DJ” is a perfect encapsulation of the album’s anxious energy, both musically and lyrically.

“Look Back in Anger”

“Look Back in Anger” is one of Lodger‘s most emotionally charged tracks, blending a sense of desperation with frenetic musical intensity. The song’s dramatic production, with its surging guitar lines and Dennis Davis’ propulsive drumming, creates a mood of mounting tension. Lyrically, it paints a picture of guilt and existential dread, as the protagonist reflects on past regrets, haunted by a mysterious angelic figure. Bowie’s vocal performance is impassioned, giving the track an emotional weight that’s hard to shake. The furious momentum of the song makes it a standout, offering one of the album’s most cathartic moments.

“Repetition”

One of the album’s most chilling tracks, “Repetition” stands out for its stark minimalism and lyrical directness. In a sea of abstract, fragmented imagery across the album, “Repetition” is a brutal depiction of domestic violence, told from the perspective of an abuser. The lyrics are unsettling in their casual detachment, with Bowie adopting a monotone delivery as he recounts the routine brutality of the situation: “He talks like a jerk, but he could eat you with a fork and spoon.”

Musically, the song is sparse, with a repetitive bassline and cold, robotic rhythm that mirrors the numb, cyclical nature of abuse. The simplicity of the arrangement makes the lyrical content even more impactful, making “Repetition” one of Lodger‘s most harrowing and unforgettable tracks.

Memorable Moments

Lodger is packed with striking moments that capture its essence—chaotic, disorienting, and boundary-pushing. These moments not only showcase Bowie’s talent but also reinforce the thematic dissonance and complexity of the album.

Adrian Belew’s Guitar on “Red Sails”

Adrian Belew’s surreal guitar work is one of the standout elements of Lodger, and nowhere is it more apparent than on “Red Sails.” The song is an eerie, almost nautical journey, with Bowie singing about sailing into unknown waters. Belew’s playing is jagged and angular, twisting the typical rock guitar into something unearthly. The dissonant riffs give the track a nervous energy, perfectly complementing Bowie’s lyrics about uncharted territories. This guitar work, along with the krautrock-inspired beat, creates a sense of adventure tinged with anxiety, making “Red Sails” one of the album’s most distinctive tracks.

Vocal Fragmentation on “African Night Flight”

One of the most chaotic moments on the album occurs during “African Night Flight,” where Bowie’s vocals become almost unhinged. He delivers frantic, staccato phrases over a collage of tribal beats and synthetic textures. The vocal delivery, which teeters on the edge of a nervous breakdown, captures the feverish disorientation of the song’s protagonist. This moment is memorable not only for its sheer energy but also for how it encapsulates the album’s theme of cultural dislocation and existential anxiety. It’s an experimental triumph that exemplifies Lodger‘s fearless approach to genre and form.

The Satirical Energy of “Boys Keep Swinging”

A particularly memorable moment comes at the end of “Boys Keep Swinging,” where the band—composed of musicians playing unfamiliar instruments—delivers a sloppy, yet triumphant outro. This rough-around-the-edges sound adds to the song’s playful subversion of masculine bravado, as if mocking the very idea of perfection that society expects from men. The chaos of the outro, with its unpolished solos, leaves a lasting impression, emphasizing that Lodger is not concerned with neat, conventional endings but instead revels in disorder.

The Ominous Silence in “Repetition”

One of Lodger‘s most powerful moments is its use of silence in “Repetition.” After Bowie coldly narrates the abuser’s actions, there is a deliberate lack of musical embellishment or dramatic flourish. The song ends abruptly, without any catharsis or resolution. This absence of a grand finale leaves the listener with a lingering sense of unease, mirroring the unresolved tension of the narrative itself. It’s a stark, minimalist technique that underlines the gravity of the song’s subject matter, making it all the more haunting.

Artistic Contribution and Innovation

Place in Genre/Industry

David Bowie’s Lodger, released in 1979, occupies a unique and somewhat complex place in both his discography and the broader music industry of the time. Coming at the tail end of his Berlin Trilogy—following the more overtly avant-garde Low and “Heroes”—Lodger stands as a bridge between Bowie’s experimental, ambient leanings and the more commercial, genre-spanning sounds he would explore in the 1980s. At a time when punk had evolved into post-punk, and New Wave was becoming a dominant force in popular music, Lodger defied easy categorization. Rather than aligning fully with these trends, Bowie continued his practice of absorbing influences from different genres, cultures, and sonic landscapes, pushing his music beyond the boundaries of conventional rock or pop.

In the context of its release, Lodger was not immediately hailed as groundbreaking; critics and fans were divided on its significance. It didn’t have the immediate impact of Low or “Heroes” in terms of radically altering the trajectory of art rock or post-punk. However, with the benefit of hindsight, Lodger’s influence can be seen rippling through the works of many artists who followed.

Its blending of art-rock, global influences, and experimental production techniques would foreshadow the genre-melding spirit that defined much of the 1980s. Bowie’s refusal to adhere to established norms, combined with his continued use of fractured song structures and cultural references, was ahead of its time, laying the groundwork for musicians who would later mix rock, electronic, and world music.

Place In Career

Though it was less commercially successful than some of Bowie’s earlier work, Lodger holds a place as a crucial stepping stone in his career—pushing him away from the purely experimental soundscapes of the Berlin Trilogy toward the more mainstream success he would achieve in the ’80s with albums like Scary Monsters (1980) and Let’s Dance (1983). Its genre-blurring approach also mirrored the broader industry trend of the late ’70s and early ’80s, where music was becoming increasingly difficult to classify, and artists were willing to experiment across multiple styles.

Innovation

One of the most innovative aspects of Lodger is its approach to genre blending and its subversive take on the typical rock album structure. Unlike its predecessors in the Berlin Trilogy, which leaned heavily into ambient and instrumental experimentation, Lodger brings Bowie back to a more song-based format—yet with a significant twist. Rather than relying on straightforward rock or pop formulas, the album is built on the fusion of disparate musical styles and influences.

Bowie pulls in elements of krautrock, post-punk, Middle Eastern melodies, and African rhythms, mixing them into a collage of sounds that feels both cohesive and disorienting. Songs like “Yassassin” and “African Night Flight” exemplify this globalized approach to music-making, predating the world music explorations that would become more prominent in pop and rock throughout the ’80s and beyond.

Themes

Thematically, Bowie’s Lodger also breaks new ground by tackling issues of displacement, identity, and cultural alienation in ways that feel fresh and prescient. While these themes aren’t new to his work, the way they are explored here—through the lens of travel and nomadism—gives the album a conceptual depth that resonates with the globalized, interconnected world that was emerging at the time.

Bowie’s nomadic protagonist on Lodger isn’t just a tourist; he is a figure caught between worlds, cultures, and identities, reflecting the anxieties of a world in transition. This thematic approach was innovative not just for its time but also in how it prefigured much of the postmodern exploration of identity in popular music, where cultural fluidity and hybridity would become increasingly important.

Production

Another key innovation on Lodger is the album’s production style, particularly the way Bowie and Brian Eno manipulated sound to create a sense of instability and unease. The decision to have musicians switch instruments on “Boys Keep Swinging,” for example, adds an intentionally rough, amateurish quality to the track, undercutting its otherwise upbeat sound with a sense of disorder. This experimental production choice highlights Bowie’s interest in deconstructing the traditional pop song and turning it into something more subversive.

Meanwhile, Adrian Belew’s unorthodox, angular guitar work—most notably on tracks like “Red Sails”—further pushes the album into avant-garde territory, eschewing typical rock guitar riffs for unpredictable and dissonant sounds. The layering of different sonic textures, from fractured funk to krautrock-inspired rhythms, makes the album a rich listening experience that reveals new details with each listen.

World Elements

Finally, Lodger stands as an early example of an artist incorporating world music elements into a Western rock album without exoticizing or diluting them. Instead of using non-Western sounds as mere embellishment, Bowie integrates them into the very fabric of the music, creating something that feels genuinely borderless. This approach to cross-cultural fusion would become a hallmark of Bowie’s work in the decades to follow, and Lodger serves as the experimental blueprint for these later explorations.

Closing Thoughts

David Bowie’s Lodger is an album that thrives on contradiction—both accessible and experimental, cohesive yet fractured. As the final chapter in his Berlin Trilogy, it marks a transition from the stark ambient soundscapes of Low and “Heroes” toward a more song-centric approach, while still embracing the avant-garde tendencies that defined his work with Brian Eno. The album’s strengths lie in its genre-defying sound, its thematic depth, and its fearless exploration of cultural and emotional dislocation. Lodger successfully blends art rock, post-punk, and world music influences in a way that feels adventurous and prescient, all while maintaining Bowie’s signature flair for reinvention.

Strengths & Weaknesses

The standout tracks—such as “Boys Keep Swinging,” “DJ,” and “Look Back in Anger”—demonstrate Bowie’s ability to take seemingly familiar pop structures and twist them into something unsettling and thought-provoking. His lyrical exploration of alienation, identity, and global instability feels as relevant today as it did in 1979, further proving Bowie’s knack for tapping into the cultural zeitgeist while staying ahead of the curve. The album’s production, too, is bold and innovative, with Brian Eno and Bowie pushing the boundaries of conventional rock instrumentation and arrangement. The result is a record that sounds purposefully unstable, much like the world it seeks to critique.

However, Lodger is not without its weaknesses. The album’s abrupt transitions and occasional dissonance may alienate some listeners, particularly those expecting a more traditional rock experience. Its fragmented nature—where tracks often feel like disconnected snapshots rather than parts of a unified whole—can make it challenging to digest in one sitting. This restlessness, while thematically fitting, sometimes makes the album feel less cohesive compared to its predecessors. Additionally, it lacks the immediate emotional impact of Bowie’s most iconic works, instead rewarding repeated listens with subtler revelations.

In the grand scope of Bowie’s career, Lodger occupies an essential but often overlooked position. While it didn’t have the immediate cultural impact of albums like Ziggy Stardust or Let’s Dance, its willingness to deconstruct genres and blend influences from around the globe makes it a forward-thinking and quietly influential work. Its place as a transitional album is part of its charm—it’s the sound of Bowie between worlds, both musically and conceptually.

Official Rating

Lodger earns a solid 8 out of 10 for its daring artistic vision, inventive production, and thematic richness. It’s an album that, while imperfect in its flow and emotional accessibility, stands out for its innovation and depth. Lodger challenges listeners, pushing them to confront themes of cultural displacement and personal alienation while engaging with a sound that remains difficult to categorize. It may not be the easiest Bowie album to love on first listen, but for those willing to dive into its complexities, it offers a rewarding, genre-bending journey.